Western Court

Published date: New Delhi, Oct 1978

View PDFThere is some spectacular courting in this unique hotel in Delhi

Western Court, an official hostelry in the heart of New Delhi, epitomises the decay of our political .system. It has become a classic symbol of everything that is corrupt, debauched and venal in our political life. Gossip about Western Court exploded into lurid fact on 20 August, when the ‘abduction’ of Mr. Suresh Ram, the defence minister Mr. Jagjivan Ram’s son, hit the headlines. Considering that Western Court is supposedly meant for members of parliament, government officials and their guests, Suresh Ram technically ought never to have used its facilities for any purpose, moral or otherwise. And yet, after darkness had fallen on 20 August Suresh Kumar was, from all indications, entertaining his lady friend, the young and comely Sushma Chowdhury, in a single-room suite on the northern side of the ground floor of Western Court.

Suresh Ram had reportedly made sure of the regular use of this room as part of a deal he struck with his friend, Mr. J. K. P. N. Singh, the ex-ruler of Maksoodpur in Bihar. Earlier this year when Suresh Ram was offered a Rajya Sabha nomination, he is reported to have offered it instead to Singh and secured the use of the Western Court room in return.

When Suresh and Sushma drove out of the Western Court grounds that evening in a borrowed black Mercedes, they were tailed by two taxi-loads of young men. Somewhere near Nigambodh Ghat the Mercedes was forced to stop, a few young men entered it, and the three-vehicle convoy then drove on towards Modinagar in Uttar Pradesh. From this blossomed the entire Suresh Ram abduction story, the details of which are public knowledge today, The Suresh Ram incident symbolises far more than one mere fracas. It is the tip of an iceberg of political hanky-panky, a jockeying for favours within our corruption-ridden system. It has all the makings of our version of the Profumo scandal. And most interestingly, it originated from Western Court.

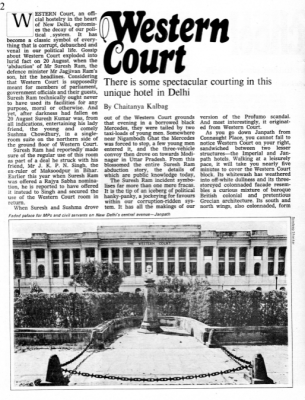

As you go down Janpath from Connaught Place, you cannot fail to notice Western Court on your right, sandwiched between two lesser structures-the Imperial and Janpath hotels. Walking at a leisurely pace, it will take you nearly five minutes to cover the Western Court block. Its whitewash has weathered into off-white dullness and its three- storeyed colonnaded facade resembles a curious mixture of baroque British colonial and pretentious Grecian architecture. Its south and north wings, also colonnaded, form the parallels of a huge square bracket.

Everything about Western Court is larger than life, strongly reminiscent of a de Mille film set. Its grounds cover an area of 8.2 acres in land-starved central Delhi. Its plinth area is an awesome 149,309 square feet. Its rooms have very high ceilings, almost 20 feet up. Its broad portico, running all along the front, is like a huge, shadow-dappled tunnel.

As though Western Court’s monstrosity were not enough, it is faced, on the opposite side of Janpath, by its twin-Eastern Court. Today Eastern Court is occupied by the Posts and Telegraphs department, and has gradually taken on the much-used and inhabited air of a government office building. It is Western Court, built in 1920-21 by Sir Sobha Singh and intended to be one of the gems that adorned Lutyens’ Delhi, which still retains its original purpose : that of a hostelry for our pen-pushers and podium-pounders, government officials and members of parliament.

In pre-independence days, Western Court’s suites-there are 19 single suites and four double suites on the ground floor, 20 and four on the first floor, and 23 and four on the second floor-were usually allotted to newly-arrived British officers who were bachelors or had left their families behind or had not been assigned bungalows elsewhere in the city. Old citizens recall that it had an air of temporariness about it, the hustle and bustle that characterise a caravanserai. There was life and traffic moving up and down its driveways, and the occasional weekend revelry.

Once in a while some Indian leaders were also accommodated at Western Court. Two plaques in the portico commemorate Pandit Motilal Nehru who stayed there between 1924 and 1926, and Lala Lajpat Rai who was there in 1926 and 1927. Some famous freedom fighters too are supposed to have been incarcerated there-in confinement resembling house-arrest.

One old bearer at Western Court has fond memories of Shyama Prasad Mookerji, who used to stay there in the early 1950s. Shyama ‘da’ although he was a central minister and entitled to more spacious accommodation, used to occupy a single-room suite on the ground floor of the south wing. The bearer re- calls that his room used to be full of visitors every morning from seven to ten, all with supplications and applications for jobs. And Shyama ‘da’, who handled the Industry portfolio in those days, would play them with tea and snacks, listen patiently and instruct his assistants to help the deserving.

Those were the days, as the old phrase goes. Today Western Court is fast going to seed. And our curious bureaucratic processes cloak it in unnecessary secrecy and security for the general public, that is. For the men in high places, for the wheelers and dealers in our political system, Western Court is familiar ground. We had to spend a few futile mornings at the Works and Housing Ministry to try and obtain permission to photograph Western Court. Later, of course, some photographs were taken with what amounted to unnecessary stealth for a place that is not a defence godown or an ammunition dump. And in order to find out just how Western Court was to live in, I managed to spend two nights there, again by using ‘connections’. That precisely is the crux of the Suresh Ram incident-if you have the proper connections, you can get to use Western Court’s facilities and its extremely convenient location for your own purposes.

Compared to the hotels that flank it, Western Court is a far cheaper alternative for any purpose. Its regular residents pay a rent of Rs 90 per month per suite, while a visitor has to pay only Rs 26 a day. Accessories like bedsheets, blankets and pillows are an extra 75 paise a day. The food, whatever its real worth may be, costs Rs 12 a day- you get a watery bed-tea which a bearer bangs grumpily down after waking you up at 6-30 a.m., break- fast, lunch, evening tea and dinner. Preferable, definitely, to the expensive hotels on either side.

The room I stayed in had not been cleaned for some time. It had a terrible smell, and I was told there had been a party there a few days before. Fish-bones were scattered over the threadbare carpet. Someone had obviously thrown up in the bathroom. And the jamadar carted out quite a few beer and whisky bottles. The plaster on the walls had peeled long ago. There was a musty smell all around. Two discarded shoes stood disconsolately in the cold fireplace. The mattress on the bed was very lumpy, there were cockroaches scuttling across the floor, the small tea-table in the centre of the room was chipped, its varnish long vanished, and the backs of the two sofas bore evidence of many oily heads. To collect drinking water I had to climb the stairs to the first floor, where a huge water cooler stood outside the dining hall. And in Western Court a walk to the dining hall is quite a journey- the distance itself is sufficient to build up one’s appetite.

I needed all the appetite I could muster to get through the food. Breakfast consisted of porridge one morning, cornflakes the next ; one banana ; two slices of toast and two eggs made to order ; and coffee or tea in pots whose spouts smelt suspiciously of cockroaches. And the menu for dinner did not change over three nights: it consisted of a passable dal, rotis, crusty and improperly baked, a sabzi made of gourd, rice and an oily mutton curry. The only recreation in the big dining hall was a television set, usually drowned out by the loud voices of the diners. The dining hall quickly acquired the noisy contours of a hostel mess, the bearers serving the courses with a surly indifference.

One bearer gave voice to his dissatisfaction. He complained that they were all poorly paid, that the residents were impolite and uncaring, that the bearers were asked to run up and down the long corridors many times a day, that the system of tipping had not reached the consciousness of the people’s representatives.

In the evenings, clusters of men and women sat around in cane chairs on the stretches of lawn in front, sipping cold drinks and gesticulating as they talked. Night fell routinely and people went indoors. I took long walks up and down the corridors, sniffing at the occasional whiff of liquor coming from behind screen doors. And at night I waited for confirmation of what a bearer had whispered to me : that women of ill repute stole along the corridors at dead of night, knocking on certain doors. My door remained unknocked.

There are whispers—many whispers—among the residents and servants in Western Court. Suresh Ram has brought the place into the public gaze and no one evidently relishes this attention. Many MPs are away in their constituencies, this being an off-session period, but those who have stayed on are taciturn, reluctant to discuss anything with inquisitive outsiders who ask embarrassing questions.

The servants, on the other hand, were willing to talk. They seemed secretly glad that Western Court was at last reaching beyond its dusty bureaucratic introversion. They spoke of the many shady goings-on in Western Court, of the booze parties that went on into the wee hours of the morning, of the ease with which one could enter the building, unseen, from any one of the many possible entry points along its front, of the dark cars that rolled up in the darkness and disgorged heavily painted and giggling creatures of the night.

One servant proudly pointed out the locked door of a room that he claimed was a favourite of both governmental and opposition circles. “Admit it, sir,” he said, “these men are after all human beings and they need occasional release. And what better place than this, where a man can quietly bring in a woman, and later depart unnoticed ?”

Indeed, if my room were any indication, Western Court seems an ideally cheap motel, very suitable for one-night stands. But the Suresh Ram incident has scared many people and the servants say nocturnal activity has almost ground to a standstill. One old man smiled wisely when I asked him if he had personally seen any suspicious goings- on. “Why should I talk about things that do not concern me ?” he asked enigmatically. “The Suresh Ram case has become public knowledge, therefore you ask these questions. How does one know what has happened in other rooms, at other times ?”

And Western Court does not always echo with the scandals of a high-class bordello. There are quite a few families staying there and those suites are very domestmic—papa in the living room with his feet propped up and reading a news paper, the kids watching television while mama cooks dinner. And there are many respectable inhabitants too —two old and famous inmates are bachelor parliamentarians Hari Vishnu Kamath, who occupies suite 47 on the first floor, and Purushottam Ganesh Mavalankar, in suite 50 on the second floor.

In June this year, Mrs. Kanta Gupta, jumped to her death from the second floor of Western Court. Her husband rushed her to hospital, but she died of injuries. A tiny news item in the next morning’s papers announced her death and quoted police as saying it was a suicide. But no suicide note was found and many people I met were of the firm opinion that it was not suicide, that it had all been hushed up quickly. Indeed, nobody seemed eager to discuss the incident and one man brusquely told me to stop looking into what was reported to be a suicide.

That was just another incident that had marred Western Court’s reputation. But the whiff of scandal, of suspicious happenings, cannot be brushed away. As I left Western Court and turned to look back at it, it seemed to symbolise, with its peeling interior and its damp-blot-ched walls, the slow but sure disintegration of our political and public morality. Last year the Central Public Works Department spent Rs 64,572 on Western Court’s maintenance and repairs. Like much else in our body politic, Western Court is an expensive anachronism but it has its defenders. “You are all spies, voyeurs,” one MP angrily burst out. I could not help feeling a bit voyeuristic, intruding on Western Court’s carefully-guarded scandals.