THE ART OF SURVIVAL

[India Today]

Published date: 15th Nov 1983

Deep inside the jungle in northernmost Mizoram, a lone man brews a tin mug of tea in the early morning haze. He is squatting on the bamboo floor of a makeshift shelter covered with banana leaves. Beneath it fails away the precipitous hillside, all 3,000 feet of it densely carpeted with bamboo and teak jungle. There is little undergrowth— the sunlight strains weakly through the canopy.

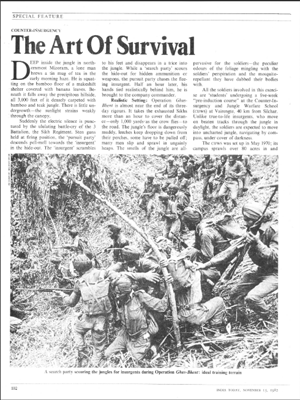

Suddenly the electric silence is punctured by the ululating battle-cry of the 3 Battalion, the Sikh Regiment. Sten guns held at firing position, the ‘pursuit party’ descends pell-mell towards the ‘insurgent’ in the hide-out. The ‘insurgent’ scrambles to his feet and disappears in a trice into the jungle. While a ‘search party’ scours the hide-out for hidden ammunition or weapons, the pursuit party chases the fleeing insurgent. Half an hour later, his hands tied realistically behind him, he is brought to the company commander.

Realistic Setting: Operation Ghus-Bhent is almost near the end of its three-day rigours. It takes the exhausted Sikhs more than an hour to cover the distance— only 1,000 yards as the crow flies—to the road. The jungle’s floor is dangerously muddy, leeches keep dropping down from their perches, some have to be pulled off; many men slip and sprawl in ungainly heaps. The smells of the jungle are all pervasive for the soldiers—the peculiar odours of the foliage mingling with the soldiers’ perspiration and the mosquito-repellant they have dabbed their bodies with.

All the soldiers involved in this exercise are ‘students’ undergoing a five-week “pre-induction course” at the Counter-Insurgency and Jungle Warfare School (CIJWS) at Vairengte, 40 km from Silchar. Unlike true-to-life insurgents, who move on beaten tracks through the jungle in daylight, the soldiers are expected to move into uncharted jungle, navigating by compass, under cover of darkness.

The CIJWS was set up in May 1970; its campus sprawls over 80 acres in and around Vairengte village. The site was chosen because, being near Mizoram’s border with Assam’s Cachar district, insurgency was not too endemic in that area, and the foothills provided ideal training terrain for the troops. By then, the Naga insurgency had been raging for 14 years, and even the Mizo revolt was four years old.

Today, the school has attained tremendous importance in the army’s operations in the North-east. Its specialised training is vital for the thousands of troops being rotated through the region every year. Indicative of this importance is the fact that the rank of the school’s commandant was upgraded last August from that of brigadier to major-general. Says Major-General Ardeshir Gustadji Minwalla, 51, the present commandant:

“The thrust of counter-insurgency was wrong in the ’60s. Troops were inducted on an ad hoc basis; the soldiers weren’t physically or mentally prepared to fight insurgency. Many of them suffered from fear of the unknown, and battles were unsatisfying ding-dong affairs. What was needed was the evolution of techniques, doctrines and concepts to fight insurgency.”

Vital Training: One of the army’s most elite schools, the CIJWS differs from other institutions because it trains entire battalions or units comprising the officers, JCO’s, NCO’S and other ranks. Foremost in the minds of the 60-odd instructors, all of whom have served “active” stints in the North-east’s insurgency-ridden areas, is the knowledge that they are training men to fight a war without strategy. “It doesn’t take a majority to make a rebellion,” the officers are told. “It takes only a few determined leaders and a sound cause.” And at the end of the five-week course, if a unit is rearing to go to its allotted base in Mizoram, Manipur, or Nagaland, it is cautioned: “Insurgencies never die. They simmer.”

A few months before a battalion arrives at Vairengte, its officers go there for a full-scale orientation course. In addition, officers of units serving in the region are sent to units elsewhere in the country to prepare those for their subsequent postings. Only recently have units’ tenures in the North-east been reduced from three to two years. By the time an entire battalion already got a good idea of what they will encounter both at the school and later on in their assigned areas of operation.

Background training for officers includes study of the school’s data bank of news clippings on insurgency, and of specific counter-insurgency operations—both successful and unsuccessful. Training films help newly arrived troops to get an overview of the task awaiting them. Three years back, the school began to teach the major languages of the insurgent regions —Nagamese in Nagaland, Manipuri in the Imphal valley, and Lushai in Mizoram— using local tutors. Officers are also assigned to study important counter-insurgency campaigns—the last course, for instance, plunged deep into a study and analysis of the Greek and Malayan insurgencies, and the Naxalbari movement at home in India.

The troops are also expected to carry out in-depth studies of the tribes they will be living with in their assigned locations. Such studies include the people’s customs, traditions, religion, dress, food, and lifestyles. .Even the lowliest soldier is taught the lie of the land he will encounter; he is already told, for instance, that in Mizoram the rivers usually run from south to north, and the hills from north to south, whereas in Nagaland the ridges run from north east to south-west. Expert trackers teach the fine art of jungle tracking—a broken line of ants here, a scratched tree-trunk there, a trampled leaf, a footprint, all help troops chase a fleeing insurgent.

Jungle Warfare: The average jawan spends three of his five weeks in the school in jungle exercises. The jungle can punish the fittest of soldiers—thick and virgin, its steamy heat drains energy rapidly. Leeches are particularly dangerous—even if one is pulled off the skin, the blood continues to flow from the tiny puncture, because the leech secretes a liquid that prevents the blood from clotting. The jungles are also home to giant mosquitoes that can induce the fatal cerebral malaria.

But the soldier is taught that he can befriend the jungle and use it to his ad vantage. The school’s motto drums this into him—”Fight the guerrilla like a guer rilla.” Apart from the peculiarities of jungle warfare and the dangers of urban insurgency like in Manipur, the soldier is classified for quick-reflex shooting at flee ting targets. He is tested for jungle survi val—how to trap and eat snakes, jackals, monkeys, or crows; how to distinguish be tween edible and poisonous mushrooms; how to make a fire using ordinary torch batteries and some wood shavings. He is also taught the guerrilla’s favourite booby traps for the soldiers — ranging from the pit filled with bamboo stakes to a trap that can yank a man off a mountain road with a heavy stone around his ankle.

Instructors show how to dig a pit, cover it with a polythene sheet, and collect water in a container inside the pit as it condenses below the sheet. In Mizoram, the soldier can make ‘tea’ by boiling the bark of the thingpui tree, get edible milk from the sap of the vuakduap tree, and water from the hollow thurpui vine. Am munition cans make excellent pressure coo kers for rice or dal. “Again and again,” says Minwalla, “we tell the men to conser ve their rations, to live off the land, to survive.” Some of the instructors are ex-guerrillas, and they make the best teachers.

Ambush: Other important training exercises carried out in the school’s realis tic “lecture halls” teach the soldier the brass tacks of counter-insurgency opera tions. A dummy village, with wire-opera ted cardboard ‘people’, is used to teach the “cordon-and-search” method where a rai ding party of soldiers surrounds the villa ge, pounces on the houses, and fires selec tively at “fleeing” insurgents, taking care

to avoid civilians and cattle. Another group of soldiers is taught how to react to the guerrilla’s favourite method of attack —the ambush. The area abounds in ideal ambush sites, and soldiers are expected to charge “into” an ambush party, guns bla zing, instead of providing easy targets on the “killing ground”.

In areas like the Mizoram theatre, army convoys on the 185 km Silchar Aizawl road have to be properly protec ted. Soldiers are taught how to sit in their one-tonne and three-tonne vehicles, guns at the ready, while a ‘point man’ stands with his sten gun planted atop the vehi cle’s cabin. The trucks have to have their overhead tarpaulins off and their tail boards down to enable quick jumps on to the road. Hours before a convoy passes, the road is “opened” by groups of soldiers who scour the bordering jungle for possi ble ambush parties. This is one of the dul lest of counter-insurgency operations, tying up hundreds of men; yet, the slightest laxi ty has often led to devastating ambushes. All that the guerrilla, in real life, needs to do is to let off a rapid, two-minute burst of machine-gun fire, or a couple of rockets, and take to his heels. The cuws also teaches soldiers the fundamentals of intelligence gathering and the importance of going into an operation with full knowledge of the terrain and the rebels’ tactics.

Mental Preparation: The most impor tant part of the training at the cuws relates to ‘Psy Ops’ (psychological opera tions)—the “hearts and minds” part of counter-insurgency. The school’s Deputy Commandant and Chief Instructor, Colo nel Prem Paul Singh, 45, is a psy-ops ex pert. “Military operations touch only the fringe of the problem,” he says. “Our aim is to isolate the hostile, both physically and mentally. Since he is dependent on the population, we have to establish our credi bility and rapport with the people. The se curity forces represent the Government. Therefore we have to ‘sell’ the Govern ment to the people.”

The school’s courses teach the soldier that the army has to carry out develop mental and administrative work in remote areas where the Government’s reach is li mited. “The onus is on us to break the barrier between the Government and the people.” says Singh. “We have to shatter myths that the people here comprise an in sular, monolithic, impregnable society. All this is jargon used by people who are ignorant and cannot deal with the ‘inhi bitors’ in communication.”

UNDERLYING the psy-ops trai ling is the vital recognition that the people of the North-east suffer from cultural shock when the security forces move into their area. Using tenets like the “manipulation of the behavioural patterns of estranged people”, the troops are taught to demonstratively erase the “eth nic variation” or the “nativistic different ial”. Ultimately, says Singh, the army ought to grow so close to the people that a soldier killed by the insurgents is mourned like a fellow-villager. “In many areas even today,” he points out, “the local army commander represents the Go vernment. A successful post commander is treated as part of the Village Council.”

The civic action training includes the inculcation of principles that help the troops meet popular aspirations and the people’s greatest needs with the greatest effort they can muster. “Be progressive,” the soldier is told. “Respect the culture and religion of the people. Create a favou rable government image Enlist the peo ple’s participation in civic action projects.”

Army Participation: Such projects may include the construction of school buildings, the building of roads, provision of football grounds and the construction of churches. Army doctors provide the only available medical aid in many areas The army is also involved actively in tran sporting essential supplies to many remote villages. Expert advice is offered on the development of proper sanitation and hy giene, terracing of fields in traditional jhum cultivation areas, and in encouraging horticulture and fish breeding. Infor mation rooms in every army camp help any interested villager communicate with the troops and the outside world. At many places, the army even tries to teach the vil lagers vocational skills.

But there are pitfalls. The US Army, says Singh, even has ‘construction batta lions’ that get annual fiscal allocations from the Government. Yet, in Vietnam, the army derived little benefit from it “seal the victory” campaign. Although it spent almost $40 million annually on con structing roads, buildings and developing agriculture, local participation was very minimal, and the Viet Cong guerrillas met no opposition when they destroyed such “enemy propagandist” facilities.

The cuws itself has tried to imple ment all its doctrines in Vairengte. Says Village Council President Zamzela: “We have always had a very good relationship with the school.” J. Lalhmachhuana, pre sident of the village’s Young Men’s Asso ciation and headmaster of the government middle school, says that much of the villa ge’s development owes itself to the school’s presence. A “services” team frequently plays football matches with the Vairengte team, and the sunken ground, levelled by army bulldozers, is ringed by villagers and jawans who participate loudly and happily in the game. Three years back, half of Vairengte (pop: 3,100) was burnt down in a fire. The school’s personnel rushed to help, and an instruc tor was later awarded a Vishisht Seva Medal for his bravery in rescuing people from the fire

Singh himself remembers the recent surrender of four guerrillas of the Mizo National Front (MNF). One of the four was apparently courting a girl in Vairengte, and struck by the school’s kindness to an old man who was rushed by it to Silchar for medical attention, and whose funeral later on it participated in, the four rebels decided to surrender to the deputy commandant personally. Some years back, says Singh, when drought hit some Mizo villages, the local post commander put his men on half-rations and. shared the food with the villagers.

Man-management: “There are no set answers to any situation,” says Major General Minwalla, “only what we percei ve. Decision-making has to be calm, logi cal and analytical, and decisions should not be taken in anger, hurry or fright.” Every two years or so, the school’s in structors are changed. “If you specialise you stagnate,” says Singh. “Therefore we change instructors. Our syllabi are not sta tic, either.” Adds Minwalla: “We function as a think-tank: conceiving, comprehend ing, analysing. We teach the troops that they should not do anything with ulterior motives; they should remember that the army is incorruptible.” Outstanding ‘gra duates’ of the school are often recalled as instructors, thus ensuring that the quality of the faculty is always maintained at the same high level.

Ultimately, however, no amount of training can help a soldier react in text book style to the hundreds of situations he may face in the field. While government spokesmen in Manipur and Mizoram insist that the insurgency has been bro ken, the facts tell a different story. The cuws is normally equipped to process about seven battalions every year. Yet, it is currently handling as many as 13 or 14 annually—an indication that far more troops are being routed into the insurgent areas than ever before. Current estimates put the total army strength in Mizoram. Manipur and Nagaland at around 15,000, and many officers feel that the number is too high. “What is the point in sending hundreds of troops jungle-bashing?” asks one. “What we need is small groups of highly skilled men. Instead, in Mizoram, pickets of the Central Reserve Police Force protect police posts. Is that effective man-management ?

Nevertheless, the cuws has already attained a reputation for being one of the best counter-insurgency schools in the world. By 1985, the school will move to a new, 300-acre site near Haflong, in the North Cachar Hills, about 150 km from its present site. Minwalla envisages regular seminars in which army commanders will participate and exchange notes, and visits to counter-insurgency schools in other countries. Already, the cuws has trained soldiers from Bhutan, Kenya, Bangladesh. Ghana, Afghanistan, Iraq, Singapore, Nepal, Sri Lanka and Botswana. “I’m truly going to enjoy my tenure here,” says Minwalla.