MIRAGE IN THE DESERT

[India Today]

Published date: 31st Jul 1983

Within a few years from now, the westernmost and thirstiest fringe of Rajasthan, along the Indo-Pakistani border, is going to be brought to life by the digging of what will be the longest irrigation canal in the world up to date. Though the climate is torrid, the soil, here too, is good. When the water reaches it, it will grow wheat, maize, oil plants, citrus, fruit, and even grapes. Two million people will live by agriculture in an area which, at present, maintains no more than 100,000 pastoralists

A Quarter-Century after Toynbee presented his vision of a green desert, the Rajasthan Main Canal (445 km in length) is only now digging tortuously into its last 250 km-and his prophecy remains a distant dream. Long stretches of the canal await earth excavation, compression and lining with brick tiles, and water in the fully complete canal is flowing only until Kilometre 280-less than two-thirds of the distance to its destination at Mohangarh, 70km north-east of Jaisalmer.

Last fortnight the Rajasthan Cabinet erected another milestone in the canal’s capricious journey, and once again overturned priorities, when it approved a project expansion that immediately added Rs 310 crore to the earlier planned expenditure of Rs 534 crore. At one stroke, the Shiv Charan Mathur ministry sanctioned the construction of five additional lift-canals on the main canal’s left bank, which would branch off from the canal’s second stage to take water to the desert districts of Jaisalmer, Jodhpur, Churn and Bikaner. The sweeping revision also added 225 km to the canal’s system and greatly lengthened the scandalous delay in completing so important a project.

Project Delays: The latest decision was merely another example of the adverse fate the project has suffered from the beginning. A month earlier, the Government had announced the suspension of 23 junior and assistant engineers for embezzlement, muster roll forgery and technical irregularities, cap ping a long period of inactivity after the Ram Singh inquiry committee, set up by the Janata ministry in 1978, turned in a devastating series of 28 reports indicting canal engineers for corruption. In September last year, the then canal minister Narendra Singh Bhati had named I93 engineers in the state Assembly for substandard construction, commission of serious technical •and financial irregularities, preparation of fake muster-rolls, forgery of documents, and overpayments to contractors.

Such facts evidently escaped Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s attention when she paid a perfunctory visit to a spot near Nachana, 135 km from canal’s end, in late April to inspect the canal’s progress. Shown up a flight of brick steps specially built into the embankment, she saw a 2,500-ft-long stretch of the canal, lined and waiting for water. On either side of this showpiece stretch, however, the canal was incomplete.

Mrs Gandhi’s visit papered over the canal’s unpleasant truths-frequently-changing• plans, political disinterest, and corruption, all sought to be excused because of the canal’s dreamed-of potential.

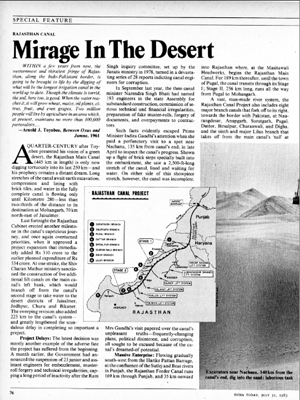

Massive Enterprise: Flowing gradually south-west from the Harike Pattan Barrage, at the confluence of the Sutlej and Beas rivers in Punjab, the Rajasthan Feeder Canal runs 169 km through Punjab, and 35 km onward into Rajasthan where, at the Masitawali Headworks, begins the Rajasthan Main Canal. For 189 km thereafter, until the town or Pugal, the canal transits through its Stage I; Stage II, 256 km long, runs all the way from Pugal to Mohangarh.

A vast, man-made river system, the Rajasthan Canal Project also includes eight major branch canals that fork off to its right, towards the border with Pakistan, at Naurangdesar, Anupgarh, Suratgarh, Pugal, Dattor, Birsalpur, Charanwali, and Digha, and the ninth and major Lilua branch that takes off from the main canal’s ‘tail’ at Mohangarh and loops downwards to west of Jaisalmer. Last fortnight’s changes added 125 km to the Lilua Branch Canal. In addition the five new lift canals will dramatically alter the geography of the canal’s left, or southern, bank, where the only major feature earlier was the Bikaner-Lunkaransar Lift Canal.

“The tragedy is that Rajasthan itself has been uninterested in completing the canal soon,” says Kanwar Sain, 84, who as chief, engineer of the erstwhile Bikaner State first conceptualised the project in 1948. “The politicians are interested in votes, and there are• no votes in the canal area.” Arid western Rajasthan, which is expected to benefit the most from the canal’s waters, has always been poorly represented politically. For instance, Jaisalmer district (area: 38,401 sq km) is almost as large as Kerala. bill its population of 2.38 lakh is represented by a lone legislator. Yet this one project, when it flowers fully, will add 30 per cent to the state’s cultivable area, bringing irrigation to 12.56 lakh hectares.

Spiralling Cost: Such political apathy was amply proved in the project’s first decade. When work began in March 1958, completion was ambitiously scheduled for 1965. Later, the target year was shifted to 1970, and then to 1985-and last fortnight, still further to 1990. Meanwhile, the project’s cost has leapt twelvefold. But between 1961 and I971, expenditure totalled only Rs 5.79 crore because of paltry allocations of funds in the state’s budgets.

Sain, who was the first chairman of the Rajasthan Canal Board in 1959, recalls that at various points the Central Government tried to take over the project in order to complete it speedily. A huge and fresh injection of finance promised by the Shah of Iran fell through when he was suddenly deposed in early 1979, and the state Government vetoed the Centre’s take-over proposals because it was reluctant to relinquish land-allocation powers. “Irrigation i’s a state subject, and so Rajasthan has adamantly refused to part with control,” says Sain.

On their part, the canal’s builders argue that their biggest hurdle has been the terrain through which they have to cut. There is hardly any population beyond Bikampur, 3 IO km along the canal, and the Rajasthan Canal Project has had to transport everything from I labourers, earth for making bricks, and Water to the construction site over long distances.

Canal Minister Chandan Mal Baid, who has been paying frequent visits to the project site, says that his priority now is to complete the main canal by March 1985- before the next assembly elections. ”For the first time,” he says. “we have all the inputs we need in plenty-money, men, material. I want to spread water to more and more land, to have extensive cultivation.”

Ambitious Plan: All the vicissitudes that the canal has had to suffer since its inception, however, have thwarted what was planned to be the raison detre of the Indus Waters Treaty, signed by India and Pakistan in 1960 to entitle India to use all the irrigational potential of the Sutlej, Beas and Ravi rivers. Of a total quantity of 17.87 million acre feet (MAF) of water usable by India. the Rajasthan Canal alone was expected to utilise 8.6 MAF. Chief Engineer Satya Pal Kashyap. ho wever, admits: “At no point so far has the canal been able to take more than 44 percent of its total discharge potential.”

Stage II of the canal, in particular, Has faced the greatest chaos because of the Government’s uncertainty. Apart from its 256-km length between Puga[ and Mohangarh, this stage also includes plans .for 3,500 km of distributaries that will cover a Cultivable Commanded Area (CCA) of 6.09 lakh hectares. But this portion of the canal’s route cuts through some of Rajasthan’s most inhospitable terrain, with a vicious rock sub stratum that impedes digging, and miles of shifting sand-dunes.

Original plans drawn up by Kanwar Sain had provision for directing all canal water to its right bank. alongside the border with Pakistan, taking advantage of the topography-a gentle slope towards the border which would facilitate simple gravity irrigation. In 1963, Sain revised his plan-taking into account the extremely sparse population on that side of the route-to allow for irrigating I.7 lakh hectares on the canal’s left bank with a series of lift canals. In 1970, however. the lift canal idea was dropped al together and it was decided to irrigate all 6.09 lakh hectares of the CCA on the canal’s right side by gravity flow.

Shifting Priorities : In 1974 the national Commission on Agriculture, in a desert development report. strongly advised against concentrating too much irrigation on the canal’s right side. Geologists had also warned that the rocky substratum on that side would either lead to eventual waterlogging and salinity, or wasteful running-off of water towards the border. The commission recommended that the canal’s water be brought to the more thickly populated and better developed flat-lands in six drought-prone districts on its left side.

After intensive surveys, in 1976 the Government decided to irrigate 2.6 lakh hectares on the canal’s left side, as the commission had suggested, with five lift canals. cutting down the CCA on the right side to only 3.5 lakh hectares. For no conceivable reason, however, this plan was vetoed by the Janata government in 1978-and revived yet again last fortnight in an interminable saga. Sain acknowledges, however, that lift canals will raise costs steeply. A minimum of I08 mw of electricity is required to lift the water in stages up ascending gradients; this is quite a problem as Rajasthan is currently passing through an acute power famine.

More than 28,000 workmen are currently at work on the canal; this year alone, consumption of raw

material is estimated at 1.27 tonnes of coal and 87.000 tonnes of cement. All along the canal route the bleak skyline is spiked by the makeshift chimneys of brick kilns that turn out tiles for the canal’s sides and floor, Such logistics have encouraged ram pant corruption. Hundreds of ‘reaches’ of 2,500 ft each have been contracted out, and each contractor is given four months to complete his work. Almost everywhere, however, work is progressing patchily and behind schedule. In collusion with some engineers, contractors have poorly compressed the soil along the canal’s sides: bricks manufactured in canalside kilns are so poor in quality that cracks are showing up in many spots.

Since thousands of bags of cement have been quietly siphoned off, lining work has been completed with weak mortar. “Government-controlled cement rates are around Rs 49 a bag,” says Jaisalmer lawyer Kishan Singh Bhati, “but here we can buy truckloads of cement stolen from the canal for as little as Rs 20 a bag.” Adds Ram Krishna Dass Gupta, who represented Kolayat constituency, near Bikaner, during the Janata regime: “Both banks of the canal breached recently at Bajju, 65 km from Bikaner, because they couldn’t even withstand the low water flow.” Says a placatory Chief Engineer Kashyap: “Corruption is an inevitable phenomenon in such a large project.” Kashyap admits that at many points the floor levels of the canal have been so shoddily coordinated that water frequently flows back- wards.

Ecology Threatened: As for will ultimately be put, the builders have chosen to ignore ecological warnings that intensive agriculture would loosen and erode the valuable and precarious topsoil that presently supports extensive grassland. “‘Almost 60 per cent of the area irrigated by the canal consists of excellent grazing land… says Narendra Singh Bhati. “The se1rnn grass that grows wild there has been found to have great nutritive value and hardiness.”

Although agriculture has wrought remarkable changes in the earliest reaches of the canal. in Ganganagar district. more than 80 per cent of the canal will flow through land that will have to be populated by settling people on newly-developed farmland. That task is formidable, and it has been en trusted to the Command Area Development Authority (CADA). created in 1974 to build an infrastructure that would use the canal’s waters efficiently in its CCA, Foremost among CADA’s priorities is water management ; it is also responsible for roadside and canalside afforestation , laying , out a labyrinth of roads throughout the canal’s command area, constructing new townships in freshly-colonised areas, and building water courses and minor channel to take canal water to each chak (irrigation area). A separate colonisation and settlement wing is in charge of allotting land to recipients.

Developed Areas: This year’. However, faced with very adverse terrain, CADA will be spending more than a third of its budget of Rs 14crore on afforestation in order to stabilise the sand-dunes. Only until Kilometre 74 of the canal, comprising Phase I of its first stage, has CADA successfully developed the command area of3.8 lakh hectares; but even here the ultimate potential is as much as 4.18 lakh hectares. Between Kilometres 74 and 189-comprising the second phase of Stage I -CADA has run up against very tough obstacles, consisting of high sand-dunes and uneven ground.

Land in Stage l was allocated to 75,000 families. “Almost 98 per cent of these families come from other regions.” says Ram Lubhaya, additional development commissioner with CADA. “But each allottee is expected to level his land-an average per-family allotment of 25 bighas or 6.25 hectares-himself, and to dig irrigation channels to take water from the canal outlets to his fields. Most of the allottees have not been able to do so because of their poverty. A pucca water course costs as much as Rs 5,680 per hectare to build.”

Poor Irrigation: Utilisation of the canal water. therefore. has been abysmal beyond Kilometre 74, in the second phase of Stage L where only 0.34 lakh hectares have been irrigated out of an ultimate potential of 1.68 lakh hectares. In Stage II, irrigation has reached an infinitesimal 0.032 lakh hectares against an ultimate potential of 6.7 lakh hectares; 3,000 refugee families displaced by the 1971 war were allotted land in this stretch. but not one of them, says Lubhaya. has so far been able to take up agriculture. As a result of these adversities, and despite World Food Programme assistance worth Rs 13 crore to provide free wheat, pulses and coo king oil to 30,000 settler families over a five-year period, many families have deserted their allotments in desperation.

During the last kharif season. farmers in the fully developed areas below Kilometre 74 grew cash crops like cotton. clusterbean. sugar-cane, and groundnut on 1.9 lakh hectares, and wheat, gram, rape and mustard on 2.35 lakh hectares in the rabi season. Garhsana. 120 km from Bikaner. is a typical newly-prosperous CADA-developed mandi. In a matter of three years, Garhsana already possesses a telephone exchange, a school, a medical centre and a thriving grain market Land in the mandi is selling for as much as Rs 1,500 a square yard, and there are two video parlours which show the latest Hindi movies.

Bad Planning: The difficuIties being encountered by CADA in developing the command area only illustrate the lopsided planning that has always plagued the canal project. Far away from Garhsana, near Mohangarh, a gang of workmen operates a huge earth-mover that is slowly digging into the tough sandy wastes. Says Foreman Harbans Singh: “If we could dampen the earth before excavating it our work would speed up immeasurably. But water supply through pipes has only recently reached Nachana. 65 km away, and here we are, roasting in this heat in our corrugated-iron trailer camps, waiting for the water, which will come after we have wasted so much time digging into the sandy soil.”

“lt is a crime against the nation to delay such an important project,” says opposition leader Bhairon Singh Shekhawat in Jaipur. “The December 1981 river waters agreement between Rajasthan. Punjab and Haryana gave Punjab all the water that was not being utilised by the Rajasthan Canal. lf there is a settlement with the Akalis by the Centre. our fear is that Punjab will prove very difficult about releasing our full quota from the Harike Pattan Barrage.”

Rajasthan has been reeling from drought for the last five years; if the canal had been completed on schedule. much of the suffering caused by famine could have been avoided. Already this year, the Rajasthan Government plans to spend Rs 160 crore on famine relief. More than 50,000 people have fled the desert districts to neighbouring states with their cattle. and more than 120 people have died because of scarcity-induced conditions like broncho-pneu monia, measles, gastroenteritis and respiratory-tract infections.

These victims will never experience the canal’s bounty. Oblivious of the urgency of the situation, the Rajasthan Canal grinds at an excruciatingly slow pace towards completion, a project that will bear fruit-if at all-only by the end of this century , a miracle of procrastination and criminal neglect.