Interview: Robert Zagha

[Business Today]

Published date: 16th Sep 2012

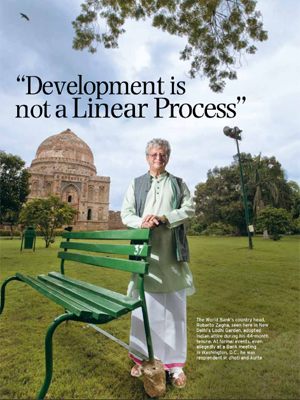

Roberto Zagha has been the World Bank’ s Country Director in India since January 2009, when the economy was reeling from the global financial crisis and just before the national elections that brought the UPA back to power.

Zagha, a Brazilian national, has been closely involved with India policy at the Bank for 17 years. During his tenure, the Bank became involved in several transformative projects; annual lending to India reached a record $9.3 billion in 2010. Days before he ended his India assignment, Zagha sat down with Chaitanya Kalbag and Sanjiv Shankaran for a frank, wide-ranging interview. Edited excerpts:

CK: What do you feel about this general air of pessimism on the economy, and why do you think there is a feeling that everything is going in the wrong direction?

RZ: When an economy grows at very high speeds – I think it was growing at 9 to 10 per cent just before the economic crisis – this is a very profound system change and that creates a lot of shocks: shocks in vested interests, shocks in established systems, established ways of operating. So, you need constant change to sustain that. To achieve this change, you need a lot of political realignment and consensus. As the economy grew and created pressure, for example, in energy and power, the fact that you had such a huge increase every year like 12 to 14 per cent increase in demand for power created a very significant stress. Now, the institutions and the systems in place were not geared towards responding to that for a variety of reasons. Coal India needs to be very responsive to demand. The tariff setting system is such that if you were to substitute Coal India coal by imported coal, you would have to factor in a new cost structure. The captive mines were not allowed to sell in the domestic market. So, you had a series of places where the regulators were not operating the way one expected them to operate (after) the reforms of the power sector in 2003. So, you need to adapt and change, and coalition politics can very easily impede that change.

CK: But you must have met people from all parts of the political spectrum. One of the things that people say for a country of India’s size is that there ought to be political consensus, that there needs to be continuity of economic policy.

RZ: That is what the prime minister has said, that it is a national security issue, and I think he is very right. The question is how do you translate that in a democratic setting. India is not unique. Look at the United States.

“You need to adapt and change, and coalition politics can easily impede that change”

They have failed massively in a variety of policy areas because it is very hard for democracies to build consensus. The same in Europe. Europe is going through an unnecessarily profound economic crisis, because people have different ideas about how to respond.

CK: There seems to be an absence of urgency and passion in terms of where we need to go. RZ: India has many gods. You just cannot push a button and resolve the power crisis. You need to bring them along. Coal India – the private mines which have been given licences to operate, the state governments, the central government. So, when you start looking at what’s needed to resolve the power crisis, it’s not beyond India’s capacity to do it. It is in a sense very easy. But when you look at the different interests and systems and institutions that need to be brought along, it becomes very difficult.

We have an interesting case with one of our own projects – the Vishnugad Pipalkoti project on the Alaknanda river. It is throwing up a whole series of issues – how do you bring different parts of society to agree on something; how they are going to use the waters going into the Ganga, which are considered sacred. So, we said at one point that if we had a power unit which would leave a minimum flow in the river, which would enable pilgrims to bathe and reach their shoulders, that would be enough. But not really, because some people feel that that would desecrate the waters. Others feel the waters are losing their health impact because if they don’t reach the rocks and go through a cement tunnel, they lose the capacity of gathering minerals. You have to respect those and as a result of that our project is paralysed until the issue is resolved even though the green tribunal has cleared the project. Now, there are 77 (hydro-electric) projects in the Himalayas which are in different stages of implementation. Any economic progress has some environmental consequences. So, society needs to decide how it is going to resolve different preferences. The bottom line is that you need to bring a lot of people to agree on important issues, and India is a very argumentative democracy.

CK: That must be frustrating in many ways.

RZ: It is not frustrating. You have to respect the way development takes place. Development is not a linear process. The simple fact that you have to increase power generates a whole series of questions about how society values progress, how society values its natural resources, how society resolves conflicts. That’s why I said there are many gods and at some point they have to agree.

So, was I frustrated? I mean, you would rather see things being resolved rather than not resolved and at the same time you have to admire the capacity of this country to have put itself together after two centuries of stagnation. Between 1750 and 1950, India barely grew in per capita terms. Less than one per cent or 0.5 per cent (annually). Over 60 years, which is two generations, not that long, you have an economy which is much more productive, able to maintain democratic systems, has achieved growth rates that are demonstrably high, has reduced poverty massively. You went from less than 10 per cent enrolment in primary education to almost 100 per cent. Still, the problems are enormous: gender disparities, sex ratios of girls and new borns, quality of education, power, water, urbanisation.

CK: India is a unique case in itself. You cannot draw parallels with any other developing economy that might have been on a similar path.

RZ: I think India is unique in that it is so large. In Brazil we have had periods of very high growth that created similar situations, But we have an area that is three and a half times that of India, and a population the size of Uttar Pradesh. So, it faces less stress.

SS: You have also talked about the “low hanging fruits” of policy…

RZ: What I meant by low hanging fruits is that there are solutions. But I don’t think you can just push a button. It is not beyond human ingenuity to resolve the power crisis. For example, today you have private mines which could easily increase production. If you increase production of coal mines, you can have better utilisation of existing thermal power. This is an easy solution. This will not by itself resolve the power crisis. The power crisis has different elements: what the situation is today, what the situation will be in five years, different roles of hydro, thermal, nuclear, and how you are going to create a system that is financially sustainable. Today you don’t have that in India. Consumers are not getting power. State electricity boards are not financially solvent. So, I cannot give you one solution.

“You need to have institutions which are more Responsive to public needs”

CK: I keep hearing farmers are willing to pay for electricity if there is assured supply. Do you think the government needs to say we are at a mature enough stage and end subsidies?

RZ: I don’t think that you can do that at one stroke…it has to be done over time. I think you need to have institutions which are more responsive to the needs of the public but have more authority in terms of their finances. On the basis of consumers being willing to pay whatever they are asked to pay, there is a need for a new equilibrium. This happens all over the world and it happens in India in a number of areas as well. Gujarat, for example, and even in Mumbai, people pay for their electricity and haven’t suffered as much. It is a pretty reliable system. Even Kolkata is doing well. So, you can see that this is not a crazy proposition. People will pay if they get the service. No city in India gets water 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Don’t even talk about the quality.

SS: There was a World Bank study on the extent of debt state electricity boards have. You have an internal group studying the problems. What have they found and what solutions have they suggested?

RZ: You will have to talk to them as I haven’t yet taken stock of that. In my perspective… clearly, number one you have to have a different system for coal. The system has to be a mix of private production, a revitalised Coal India, and imports. That means the price of coal needs to be more market based. And if the price of coal is more market based then you need thermal power companies, generators which can reflect these higher costs. Which means regulators which are more ready to balance the interests of consumers and producers. And you need to have them more attuned to the interests of the producers. You cannot ask producers to produce power at a loss. This is what has been happening. So, that is one set of issues. The other is the environmental dimension…Coal happens to be in protected forest areas or where the tribals are. So, what do you do? Destroy the forests? Or destroy them temporarily and restore them? These are issues that need solutions.

SS: You plan to almost double the India funding from $14 billion to $25 billion. There seems to be a change in the World Bank’s approach because you are clearly looking at transformational projects, like the Dedicated Freight Corridor at the eastern end. Why these huge projects?

RZ: When you look at the six decades of the Bank in India, what always impresses me is that my predecessors have been doing a remarkable job of putting the Bank where it is most useful to India. So, when you look at the 1950s…what I found remarkable is that when you look at the pillars of India’s development, the World Bank has been present (for) most of them. The first loan of the Bank was for the Railways. We had 20 loans and the last request was in 1991, and it was turned down because we wanted the Railways to do very simple accounting reforms – not structural reforms. And that is when we stopped lending to Indian Railways and started lending only to offshoots of the Railways like the Container Corporation.

The general point is that the Bank was where the action was. In the 1950s, ’60s, ’70s, you name it, the Bank was present. The creation of India’s financial sector–there is hardly one financial institution where the Bank has not been associated at one point or the other. ICICI, IDBI, HDFC, IL&FS, NABARD and so on and so forth. The manufacturing sector – again there is hardly one public sector enterprise where the Bank has not been involved. Cement Corporation of India, Indian Oil Corporation, SAIL, HPCL…

When India started focusing on education, the Bank was very instrumental and this involved changing, because the Bank was evolving over time with respect to sectors, projects etc and we were engaging in some of the formative projects. For example, in Uttar Pradesh, we have a small health project which tries to improve the efficiency of public sector spending, which is 20 times as large as the Bank’s project.

CK: Have those kinds of projects actually catalysed the way the Indian government handles the larger projects in the same domain? RZ: That is the goal. It is a bit early to say success has been achieved. The Ministry of Finance has developed a kind of strategy called Finance Plus in which it expects multilateral institutions, not just the Bank, but ADB (Asian Development Bank) or JICA (Japan International Cooperation Agency), to have not only financing but also system change and transformation. Sometimes we play a larger role to achieve the objective, sometimes we don’t.

“MORE AND MORE YOU SEE BANK PROJECT BEING PROJECTS BEING USED AS AGENTS OF SYSTEM CHANGE”

But when you speak about the doubling in lending, the reason was essentially that India was accelerating its responses to developmental challenges and expanding in infrastructure investments, expanding investments in education, expanding investments in environment. More and more you see Bank projects being used as agents of system change. To go back to the example of the railways, the bank was financing projects like tracks and locomotives and so on. But over time it became clear that what was needed was more profound institutional re- forms. We moved out of the railways when it wasn’t willing to do this.

When the Bank was created (in 1944) the focus was the reconstruction of Europe and Japan. Institutions were present. What you needed was capital. There was not much thought given to institution-building, systems, the soft part of development. In the 1950s, 60s and 70s, as we started moving towards developing countries where the transformation of societies had not yet happened, the focus on policies and institutions became much more important. Therefore, we are much more concerned about financial management systems because we want to make sure re- sources are being used for intended purposes.

SS: You have had this problem in South Asia regarding siphoning of funds. Your transparency unit feels abuse of power is a very big issue in corruption. What kind of design changes have you brought about because three or four years ago you had a big problem with health sector funding here?

RZ: You know better than any bank official the problems associated with the delivery of public services. There are two things that are very important. One is corruption, when people misbehave. The other, you cannot call it corruption, but it is equally serious in developmental terms when people don’t do what they are supposed to do. For instance, when a power plant is not being maintained properly. This is not corruption, but is not an accountable, responsible use of public resources. So, the Bank has tried to put in checks and balances in the design of projects. Most bank projects, you have an ombudsman and a grievance redressal mechanism.…So, accountability is a very important concept that evolves over time. Look at the Us today. Who’s accountable for the financial crisis of 2008? Very few bankers ended up in prison.

CK: In general, there is a feeling that things have started to reach a boiling point in India in terms of corruption. Is that true?

RZ: I don’t think so. People are more indignant about it. The system is less tolerant about it. India has more money than opportunities.