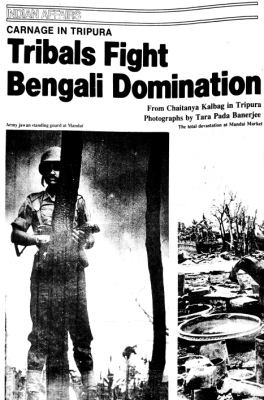

CARNAGE IN TRIPURA : Tribals Fight Bengali Domination

Published date: 23rd Jun- 6th Jul 1980, New Delhi

View PDFThe first spark flew on 6 June. A Bengali shopkeeper at Lembucchara, 8 km from Agartala, lent a tribal friend of his a dao (sickle) to cut a pineapple with. Joking about the sickle’s blunt edge, the tribal tossed it back to the shopkeeper. It hit another tribal standing close by, wounding him negligibly. But in the outcry that ensued, three Bengali shops were smashed and ransacked. Within minutes. a furlong down the road, eight tribal houses were burnt. The trouble began to spread down the Assam-Agartala road. For months, tension between the tribals and the Bengalis had built Tripura up into a giant stack of kindling. Lembucchara lit it.

Two incidents preceded Lembuchara, but they did not excite such murderous passion. On 2 June at Ampinagar, a Bengali called Nripen Chak raborty (which is also the name of Tripura’s chief minister) was killed in a quarrel with tribal boys The Tripura Upajati Juba Samiti (TUJS), the tribals’ aggressive political organisation, had launched an anti-foreigner agitation on the lines of the one in Assam. TUJS boys had issued a call for a week-long ‘bazar bunch’ from 1 June. On 6 June at Amarpur, a subdivisional headquarter in the South District, 30 TUJS members tried to close the bazar down. The shopkeepers there resisted. There was a nasty fight, which left two tribals dead

The Lembucchara incident, however, set off a chain reaction in a south-easterly direction. In towns and villages along the highway, there was arson, rowdyism, violence, and a few deaths. The next afternoon, the riots engulfed the Jirania police station area in the Sadar subdivision. Mandai lies within Jirania’s jurisdiction.

Mandai was a small marketplace about 35 km from Agartala, some distance off the highway down a rough brick-paved road. Surrounded by tribal huts, it nestled in a natural depresston, green vegetation on the left, paddy fields on the right. Mandai supported a population of nearly 600 Bengalis. Mandai was: it no longer exists. On 7 June, it was erased from the map.

At about 3 pm that day, a large number of tribals, led by some local TUJS men, descended on the marketplace. They herded all the Bengalis together. Their leader, Joykumar Deb Burma, told them they had nothing to fear-he would protect them. The mob systematically looted the settlement, including the local office of the Large- scale Anchalik Multi-Purpose Society (LAMPS). Mandai was then set on fire.

As dusk descended, the tribals turned on the Bengalis themselves. Es- struck into the panic-stricken crowd, letting loose an awesome letting loose an awesome weaponry—arrows, daus, takkals, (double-edged choppers used by the tribals in their shifting cultivation) and country-made guns. No one was spared, not even the smallest child. The massacre was carried out at faultless speed. One constable from the Mandai police outpost—a tribal—grabbed some rifles and joined the attackers. His four colleagues fled. By nightfall, stacks of bodies lay around the totally burnt- down marketplace. Many victims were backed down as they tried to flee into nearby fields. Only a hundred and odd managed to escape. More than 130 badly wounded Bengalis reached civilisation only the next morning.

It was late the next day that news of the Mandai carnage reached authorities. Even then, an Army unit led by Major R Rajamani reached Mandai only at 9 am on 9 June. It was greeted by a gruesome sight. “There were bodies everywhere,” said Major Rajamani when I met him on 14 June. Close to breaking down, he said he did not want to visit Mandai ever again—”I can’t forget the sight. One six month old baby had been cut in half from head to feet and each half had been placed neatly on either side of its mother’s body.” The Army could not satisfactorily explain why peace-keeping forces had reached Mandai more than 36 hours after the massacre. Mihir Kanti Das, sub-inspector of police in charge of the Jiraniya police station, said he was away in Kabrakhamar, 18 km west of Jiraniya, on the day the incident occurred.

Das said tribals from Charbharia, Tuipathar, Kairai and the Mandai road side made up the attacking force There were more than 500 of them. 30 shops were gutted. He was certain that the attackers were led by the local MLA, Rachiram Deb Barma-who happens to belong to the CPI(M). Deb Barma’s involvement is vehemently denied by his comrades.

State education minister Dasarath Deb, the No 2 in the cabinet, was away in Chailenta on the day the Lembuchara incident broke out. Chief minister Nripen Chakraborty was in Delhi that day. Deb rushed back early on 7 June to Agartala. After the Lembuchara incident, trouble spread quickly through the Sadar subdivision, to Bolting bagan, Nripendra nagar Colony and Nandannagar. On the road to Agartala, Deb says he saw people standing beside the road, angry and tense. The non-tribals quickly retaliated. A bus was stopped at Khayerpur and a couple of tribals were killed. Immediately on reaching Agartala Deb sent a message to Governor L P Singh in Shillong asking him to deploy the Army and to issue shoot-at-sight orders. Why did the government not take immediate steps to protect potential trouble spots like Mandai? Both Deb and Chakraborty admit that they did not have enough police to deal with the situation.

A week after Mandai’s mini-genocide, the marketplace was still smouldering. Heavy rainfall had obliterated many traces of the recent tragedy, but the systematic destruction was evident. Not a single cane-and-thatch structure in Mandai was left standing. Only a half-built school and the looted office of the cooperative society-whose almirahs had been smashed open to get at the money-both of which were of brick, stood above the levelled landscape. Some bodies had been buried in shallow graves along the roadside, and dogs were picking away at them. All along the unsurfaced and winding road to Mandai, lined by thick bushes, we had passed an unending row of burntout houses. The air was heavy with the smell of stale smoke and decomposing flesh. Even from the highway to Jiraniya and beyond, the destruction was visible from the half-charred trees that bordered burnt houses.

The state government has officially stated that 212 people were killed at Mandai, and a total of 350 through the state. It is clear, however, that the body count has been incorrect. Hundreds of bodies must still be lying in flooded fields and in the dense shrubbery and jungle that carpets much of the affected area. Intelligence sources estimate that more than 1,000 people have died; the largest number of casualties were at Mandai.

The Mandai outrage extended the violence to the nearby villages of Kabrakhamar. Borakha, Kalinagar, Lalit-bazar. Briddhanagar, Champaknagar. Jiraniaphula, Sachindra nagar Colony, Radhapur, Bisrambari, Kalabagan, and Dalbari. Everywhere, houses were set on fire, property was looted, and people who did not flee quickly enough were butchered mercilessly. The Bengalis, egged on by Amra Bangali elements (who in turn are known to be under the tutelage of the Ananda Marg) retaliated at some places against the tribals. But there were more Bengali dead. Amarpur subdivision, which has the largest tribal population in Tripura, was witness to some brutal encounters. The larger conflagration ended with violence and death at Ampinagar, Amarpur, and Teliamura.

The torching of Tripura that occured in early June was not entirely unexpected. For years, tensions between the tribals and the non-tribals had accumulated, and the pressure had to vent itself sooner or later. Exactly a year before these riots, on 9 and 10 June 1979, Teliamura and Kalyanpur had been rocked by riots that left 17 dead and 600 houses burnt. On August 8 last year, elements of the Tripura National Volunteers Forces (TNVF), also called the Tripur Sena, had participated with some Mizo rebels in a daring daylight attack on Amarpur. The portents had been many; nobody had paid much attention to them.

The extent of the cruelty and mindless destruction that had been unleashed was most visible at the 370-bed GB Hospital at Agartala. Here, all tuberculosis, cancer, and maternity wards had stopped taking in patients in order to accommodate the unending stream of victims of the violence who staggered in. There were 308 badly wounded people in the hospital’s wards on 14 June. Dr HS Roy Chowdhury, head of the department of surgery, led the way to some of the worst cases. At Jiraniya’s Primary Health Centre, he said, official post-mortems on 9 June had totalled 215 – all victims of the Mandai attack. Twenty people had died at GB Hospital itself.

The hospital overflowed with horrifying evidence of the inhumanity of the week before. The attackers had only one aim-to decapitate or butcher their victims. Tripur Sena volunteers at Mandai for instance hacked at the Bengalis’ necks and faces with their takkals. Many women patients at the hospital will emerge scarred for life—their faces have been slashed, and many of them have been raped. Orphans and widows, still in deep shock and pain, unable to comprehend the enormity of the calamity that had overtaken them, filled the wards. Dr Roy Chowdhury said the attackers had used some poisonous liquid to coat their weapons—all wounds had been rapidly and agonisingly infected and were healing too slowly. Throats had been hacked at, sometimes nearly severing windpipes.

The array of injuries at GB Hospital was sickening. Patients had been given mattresses on the hospital floors. A small team of doctors and nurses had come from West Bengal to render aid, but they were all too insufficient. There was an acute shortage of anti-cholera vaccine, they complained. They could not say how many injured people had died for lack of medical attention in the countryside, or how many bodies had been unclaimed.

By 15 June, the number of refugees in Tripura had grown to more than 160,000—out of a total population of about 18 lakhs. Both tribals and non-tribals had fled their dwellings in panic, many hiding out for days in the jungles, on the verge of starvation. Among the refugees were nearly 9,000 tribals who had fled the Bengalis’ reprisal raids. 109 relief camps had been set up for the refugees, 12 of them for the tribals.

Hatred and bitterness

The hatred that had overnight grown to gigantic proportions between the communities manifested itself even at the hospital. One tribal patient had been set upon and killed in a general ward soon after he was admitted. Another patient, a policeman, who was sent there for a bad tooth infection that had inflamed his face and given him vaguely tribal features—he was not even a Tripura man but a Rajasthani—was taken for a Mizo by a staff nurse who raised an outcry. The hapless policeman was badly beaten up. The tribal patients had thereupon been segregated from the rest.

Tribals had never taken up petty trading— even tea shops and paan shops were run by the Bengalis, who were the state’s shopkeepers. When the violence erupted, the Bengalis fled with their goods, suddenly cutting off supplies of vital commodities to tribal communities. The Bengalis had ventured into predominantly tribal areas to set up markets sometimes a market had only one or two shops, sometimes many more, like at Mandai. The situation soon turned desperate. Salt became so scarce that it was selling for Rs 15 a kilogram. On 13 June, the state had only 4,000 tonnes of rice—against its monthly requirement of 11,000 tonnes. The chief minister made an urgent appeal to the Centre to airdrop rice supplies. But with the harvesting in Tripura disrupted by the riots, the fresh crop of rice that would have augmented reserves is now largely lost.

The relief camps themselves were scenes of bitterness and suffering, potential cauldrons in which more trouble could brew. The Congress(I)’s National Students Union of India (NSUI), the Amra Bangalis, helped by the Ananda Marg, the CPI(M), and other political organisations ran different camps – and there was the accompanying political hysteria.

The Majlispur relief camp, set up at Madhabbari, close to Jiraniya on 12 June, had filled with 6,000 tribals up- rooted by the trouble. Protection was provided by a few constables of the Rajasthan Armed Constabulary (RAC), some of whom have been in Tripura for over six years now. Military doctors were visiting camps daily, but medical attention was inadequate and cursory. The tribals at Madhabbari said that hundreds of their community had fled from Radha mohanpur, Jiraniakhola, Madhabbari and Paschim Borjala when they were attacked by Amra Bangali ‘fanatics’. Sunil Dutta, a quiet unobtrusive Bengali who owns photo studios at Jiraniya and Mohanpur, was responsible for reporting the plight of around 850 fleeing tribals to the police on 11 June. To the tribals, Dutta was a hero, a Bengali who had not turned upon them like the others.

When I reached the Ranir Bazar Vidya Mandir relief camp, Tripura’s revenue minister Biren Dutta zoomed in with a cavalcade of cars and a police van. It was the first time – more than a week after the trouble began – that a state minister had visited any relief camp. Dutta was at once mobbed by angry Bengalis, and beat a hasty retreat. The Ranir Bazar camp was run by NSUI(I) volunteers. More than 4,000 Bengalis had flocked there for shelter from Burakha, Kalikapur, Kabrakhamar, Asthalonga, Chakbasta, Durganagar, Tathua, Kawabari, and Majlispur. The camp opened on 7 June. Monoranjan Debnath, general secretary of the school’s students council, and Narayan Chandra Chowdhury of Chakbasta (where, at the huge pink-facaded engineering college, the Army had set up a local base camp) were very angry about the minister’s belated visit. “The government’s tribal stooge, Dasarath Deb, incited his followers to attack us,” they said. “And now they are coming to check up on how much our people have suffered.” Dasarath Deb, the state’s education minister, who is a Tripuri tribal (who comprise the largest tribal group in Tripura) on the other hand complained bitterly that the tribals called him Bangalir dalal (Bengalis’ agent) while the Bengalis accused him of inciting the tribals to attack them. “There is a door-to-door campaign on to vilify me,” he said.

In Tripura, the story is once again one of the inevitable reaction of the local inhabitants to a tidal influx of new settlers from outside. Surrounded on three sides by Bangladesh, Tripura is linked tenuously to India by a tiny border with Assam and Mizoram. The trickle of immigrants from East Bengal before Partition swelled to a flood after 1947, when hundreds of thousands of Hindu refugees from East. Pakistan crossed over into Tripura from the Sylhet, Comilla, Naokhali and Chittagong districts.

Prior to Partition, the tribals of Tripura – Tripuris, Chakmas, Reangs, Halams, Jamatias, and at least 13 other groupings-comprised 78 per cent of the population. Partition forever altered the demographic structure. Tripura’s population, which was 5.13 lakhs in 1941, shot up to 15.56 lakhs by 1971. Today it is close to 18 lakhs. In 1971, there were only 29 percent tribals. Today the tribals have been reduced to only 25 per cent of the population. When Tripura became a full- fledged state in 1972, its Assembly seats were statutorily raised to 60, 19 of which were reserved for the tribals according to their proportion in the population. By 1977, when the last Assembly elections were held, the tribals’ seats had dropped to 17. The tribals have therefore understandably been gripped by a rising feeling of insecurity.

Tripura was a princely state until 15 October 1949, when it merged with the Indian Union. Until then, the Congress party did not enjoy any support there. Maharaja Bir Bikram Kishore Manikya Bahadur’s only political venture consisted of the Tripur Sangha, which he formed in 1945 shortly before he died. The Tripura Sangha, whose leaders belonged mostly to the royal family, was revived by the Congress in 1949. Bir Bikram’s son Kirti Bikram oversaw Tripura’s merger with India.

The Communists first gained a foothold in Tripura in 1950, when many West Bengal Communist Party of India (CPI) members on the run from the authorities there took shelter in the dense forests of Tripura’s North District. Dasarath Deb, who formed the Upajati Gana Mukti Parishad (UGMP) for the educational and poli- tical uplift of the tribals. in 1949 and launched armed struggle against the king. provided a ready base for the then undivided CPI. Deb joined the CPI, but his revolutionary ideals were clearly not well-formed, for the CPI deputed Nripen Chakraborty. then 45 years old and one of West Bengal’s most promising Communists- Chakraborty is considerably senior to Jyoti Basu-in October 1950 to Tripura to help shape that state’s infant unit of the CPI. To this day. Deb and Chakraborty are the state’s major Communist leaders. Deb has still not disbanded the UGMP, which is now a largely social-welfare organisation.

In 1954, the Congress encouraged a tribal leader, Sneha Kumar Chakma, to form the Tripura Tribal Union. Chakma raised the demand for a Hill State that would have no Bengali immigrants in it. He campaigned the 195 7 and 1962 Lok Sabha elections (Tripura had, and still has, two seats in that House) but lost heavily to the CPI. In 1963, Chakma and his followers joined the Congress Party. Between 1962 and 1966, when Deb and other Tripura CPI leaders were in prison under the Defence of India Rules (DIR), Chakma and the Congress tried hard to woo the tribals to the Congress fold.

Although the Congress was in power in Tripura for 25 years until 1977, the Communists were steadily gaining in strength. Tripura’s Communist MPs, Dasarath Deb and Biren Dutta, who consistently won both Lok Sabha seats, very very vocal about the tribals’ cause and objected to the continuing influx of refugees from East Pakistan. When the CPI split in 1964 into the CPI and the CPI(M), Deb and Dutta, along with Chakraborty, took their large following over to the latter party. Worried about the CPI(M)’s increasing influence, the Congress chief minister, Sachindra Lal Singh, backed the formation of the Tripura Upajati Juba Samiti (TUJS) in 1967.

The TUJS’s major constituents were the Chakma and Jamatia tribes, while the Tripuris, the largest tribe, were sol- idly aligned with the CPI(M). The tribals, who practised shifting or joom cultivation (slashing and burning vegetation on a hillside, growing a crop there, then moving on to the next hill) were affected by two important developments. The Congress regime in 1975 banned shifting cultivation. Secondly, land that the tribals had previously sold at ridiculously low prices to the incoming Bengali settlers suddenly acquired new value as the tribals began to go in for fixed (plough) cultivation. The land pressure began to near exploding point.

In 1960 Parliament had passed the Tripura Land Revenue and Land Reform Act, which regularised the land- holdings and provided for protection of tribal land. In 1941, the then king had set up Tribal Reserve Areas, but these were eroded by succeeding waves of immigrants. The 1960 Act carried a Communist-sponsored amendment which said tribal lands could be transferred to non-tribals only with the state government’s approval. This increased support for the Communists, but did not deter illegal sales of tribal land to the Bengalis.

In 1974 Congress chief minister Sukhomoy Sengupta compounded the Congress alienation from the tribals by amending the 1960 Act to read that all Tribal Areas were thence forth derecognised. The CPI(M) united with the TUJS and the still-extant UGMP to protest.

The Bengalis in Tripura, unlike in West Bengal, had traditionally supported the Congress because of the CPI(M)’s championing of the tribal cause. After Indira Gandhi’s government fell in March 1977, Tripura pas- sed through two disastrous and short-lived coalition governments-the first led by the Congress for Democracy (CFD) and. the second led by the Janata. Fresh elections were held for the Tripura Assembly in late December 1977. The results were astounding. Out of the 60 seats. the CPI(M) won 53, and its Left Front partners won 3. The remaining four seats went to the TUJS, which entered the legislature for the first time. The Congress was totally routed.

It was after the Left Front government assumed office on 5 January 1978 that the problems began. Caught between its commitment to the tribal cause and the realisation that the larger number of votes came from the Bengalis, the state government began a dangerous stint of tightrope walking. But the tribal pressures were too immense. In July 1979, the President of India approved the Tripura Tribal Areas Autonomous District Council Act, passed earlier by the Tripura Assembly, which provided for the establishment of a semi-autonomous Tribal Council that would cover two-thirds of Tripura’s area of 10,477 sq km.

The Act was placed in the Constitution’s Seventh Schedule, which meant the Council would enjoy largely municipal powers, aside from control over trading within its limits and the medium of instruction in tribal schools. Bengali was the medium of instruction, and Kokborok, the tribal language, had been either not taught or ignored altogether.

The foreign hand

The TUJS was unhappy with the Act-it wanted a Sixth Schedule listing for the Council, which would place it directly under the Governor’s, and therefore the Centre’s, jurisdiction. The TUJS stepped up its anti-immigrant anti-Bengali campaign. The Bengalis, mainly the Amra Bangali group, launched a counter-campaign against the Act because they feared they would be eventually forced into a corner and then squeezed out of Tripura. The Bengalis pointed to the example of Meghalaya, which originally was a Tribal District Council within Assam and where tribal demands for separate statehood finally succeeded.

After the destruction began on 6 June and continued sporadically there- after, official action was sadly inadequate and concerned more with political expediency. Union Home Minister Zail Singh, who rushed to Tripura on 11 June and flew over the affected areas, returned to Delhi to bemoan the cruelty and suffering he had seen but said the Left Front government would not be touched. Later, he suddenly reversed his stance and accused chief minister Nripen Chakraborty of inciting the tribals in the state. Every evening at Agartala, meanwhile, Chakraborty held press conferences at the red-brick Secretariat where he brought the visiting journalists up to date on deaths, fresh attacks, arrests, and security arrangements. Chakraborty angrily reacted to Zail Singh’s allegations and countered by saying that intelligence reports on the brewing trouble had been ignored by the Centre, which had failed to send adequate armed protection or other material aid.

Chakraborty also tried to prove that the tribal attackers had been armed and trained by Church and foreign agents. Although Tripura has many Christian missionaries and quite a few Baptist schools, 89.5 per cent of its population is Hindu. On 14 June, Chakraborty showed newsmen ten inch long incendiary sticks, of obvious foreign manufacture, which he said had been tied to arrows, lit, and fired at Bengali houses. He read excerpts from documents listing ‘extremists’ and said that money from abroad had been channelled into Tripura through New Zealand-Rs 7 lakhs during 1978 and Rs 14 lakhs during 1979.

The Tripur Sena (later called the Tripura National Volunteer Force-TNVF), the most militant of the tribal extremist units, does have links with Mizo and Bangladeshi rebels, and is supposed to have a vaguely Maoist ideology; it was formed in early 1978. Nripen Chakraborty was accused of leniency towards and indirect encouragement of the TNVFs “General”, Bijoy Kumar Hrankhal, who was arrested on 13 June at Ambasa. Chakraborty vehemently denies this.

Hrankhal, 47, was educated at Christian schools in Tripura and Shilong. He joined the TUJS in 1967 and became its chief, but secretly organised an underground ‘army’, for which he was suspended from the TUJS. He then formed the TNVF. Sixty-five of his boys were sent to Bangladesh for training; two were arrested last year while returning to Tripura. The state government increased efforts to capture Hrankhal.

Hrankhal is said to have written two letters to Chakraborty early this year offering to lay down arms and adopt democratic methods. Chakraborty thereupon reportedly ordered that arrest warrants issued against Hrankhal be not enforced. He met Hrankhal secretly on 16 February this year, when there was a solar eclipse and Agartala was largely deserted. After this meeting, Hrankhal reportedly began to overtly organise TNVF cadres for revolt. The TNVFs chief aim is to carry out armed struggle to ‘liberate’ Tripura.

No foreign arms have yet been seized; only 50 guns, mostly country-made, have been captured. Tripura has an inordinately large number of licensed arms in circulation. Although the Congress governments there had routinely issued licenses for guns to tribals-for whom owning a gun is a status symbol-the CPI(M) government is believed to have issued more than 5,000 licenses after it took over in 1978.

Until 15 June, more than 850 persons had been arrested, most of them TUJS or TNVF members; among them were Buddha Deb Barma, president of the TUJS, Syama Charan Tripathi, the TUJS’s general secretary, and Ratimohan Jamatia, TUJS MLA from West Tripura. Anil Debnath, the leader of the Amra Bangalis, was also arrested. The TUJS is also alleged to be linked to the shadowy Forum of Hill Regional Parties of North-east India, which is reportedly coordinating extremist elements in the seven north- eastern states.

Other tribal organisations accused of involvement in the carnage are the Sangrak Party-a rag-tag army-the Tripura Students Federation (TSF) the TUJS’s student faction, and the Tripura Sundari Bahini, a militant women’s body (Tripura Sundari is the name of the goddess at the popular Kali temple at Udaypur).

Jutting precariously out from north-eastern India into Bangladesh, Tripura’s borders are impossible to seal. Sixty per cent of its land area is covered by forests. The local police, the Tripura Armed Police (TAP), the Rajasthan Armed Constabulary, the Army, the Border Security Force and the Central Reserve Police Force units in the state have been strengthened, but static or fixed pickets to protect affected areas, and organised combing operations, are impossible considering both the terrain and the atrociously bad roads (the state has only 1,251 km of surfaced roads). Intelligence sources say that if telephone lines had been cut in the recent disturbances the situation may have been uncontrollable.

Ten days after Lembuchara, murder, arson and rioting continued to rock Tripura sporadically. The passions aroused would not allow normalcy to be restored for quite some time. Even if normalcy were to return, the bitter memories of Mandai and other atrocities among both tribals and non-tribals would endure. India’s second-smallest state seemed to be teetering on the brink of a larger holocaust. Worst still, one more sordid chapter had been added to the tragedy of the north-east, penned in cold blood.