ASSAM: Over The Edge

Published date: 12th May 1980, New Delhi

INTRACTABLE and increasingly aggressive, the Assam agitation last fortnight edged closer to ugly confrontation. The deadline for a Central government decision on the foreigners issue set by the All Assam Stu- dents Union (AASU) and the Gana San- gram Parishad (GSP) expired on May 15 with no sign of progress except an offer by Prime Minister Indira Gandhi on May 11 of renewed talks with no specific cut-off year. On May 14, Central and State government officials, and employees of semi-government establishments, banks and private offices all over Assam walked out of work in protest against the “repressive measures” and “victimisation” of participants in the movement. The North East Region Students Union (NERSU) meanwhile intensified liaison with the six neighbouring states and union territories and the bush fire that had begun in Assam seemed to be spreading rapidly through the entire Northeast.

H C Sarin, principal adviser to the Governor, who arrived to take charge in April tried valiantly to put a semblance of discipline in the state administration. Dismissed Chief Secretary R S Paramasivam, who has been posted to the Cabinet Secretariat in Delhi, had left behind a legacy of neglect and chaos. His successor, Ramesh Chandra, and Sarin together ploughed on, regardless of largely empty government offices. Sarin has been named by sources as the next possible governor of Assam, a reorganisation that would leave present incumbent LP Singh four states – Manipur, Meghalaya, Nagaland and Tripura. Meanwhile, danger signals mushroomed.

A secret underground society reportedly put out a 35-point programme for total revolution. This was denied and ascribed to agents provocateur by agitation leaders.

On May 16, AASU president Prafulla Mohanto – supposedly in hiding but highly eloquent in recent weeks – and acting general secretary Bharat Narah spelt out a two-phase programme: preparation of a citizens’ register by collecting details in forms distributed by AASU’s activists, and subsequent deportation of foreigners on its basis by AASU itself, if the government “did not act”. This followed declaration of Direct Action by the agitationists the previous day.

Seven persons were arrested in Gauhati after volunteers of the GSP wrongly con- fined’ 13 labourers travelling by boat on the Brahmaputra on May 11, accusing them of being foreigners.

Citizenship would be proved, agitation leaders said, if a person could show his or his ‘forefathers’ names on the National Register of Citizenship of 1951 or the electoral rolls of 1952. Proof of citizenship would have to be according to “constitutional provisions.” Finally, citizens would have to possess legal documents showing their acquisition of citizenship.

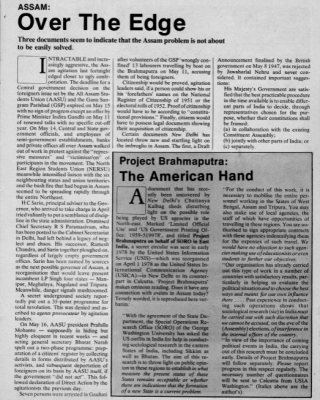

Certain documents New Delhi has located throw new and startling light on the imbroglio in Assam. The first, a Draft Announcement finalised by the British government on May 8 1947, was rejected by Jawaharlal Nehru and never considered. It contained important suggestions:

His Majesty’s Government are satisfied that the best practicable procedure in the time available is to enable different parts of India to decide, through representatives chosen for the purpose, whether their constitutions shall be framed:

(a) in collaboration with the existing

Constituent Assembly;

(b) jointly with other parts of India; or

(c) separately.

These decisions cannot be taken by the existing Provincial Legislative Assemblies. The composition of these Assemblies is weighted to give special protection to minorities and does not therefore correctly reflect the true balance of the different elements in the population. (In some Provinces) where there are large and compact minority elements, a decision by the Provincial Legislative Assembly might have the result that large areas would be brought against their will under a Constitution unacceptable to them.

In Assam, the Legislative Assembly will be asked to sit in two parts, one consisting of members elected from territorial constituencies included in Sylhet District, and the other of members elected from the remainder of the Province … The representatives of Assam (with or without Sylhet) will decide by a simple majority vote on be- half of the area which they represent, which of the three options in paragraph 1 above they choose.

Does this mean that Nehru blocked an Assamese option to stay outside India? This is what leaders of the agitation allege, and the document, which is in the India Office Library in London, seems to corroborate their grouse, although it was only a draft and was never implemented. The second document, a cyclostyled pamphlet in the Assamese language dis- tributed in Gauhati recently, is rhetorically titled ‘Who is a jaroj (bastard)?’ and makes interesting reading-

When a child has a number of fathers (that is, the mother is a harlot) it is called a bastard. We can recognise various kinds of bastards amongst us in the current movement in Assam.

Definitions of a bastrd:

– one who participates in the movement out of self-interest;

– one who does not help the cause of the movement to save the motherland;

– one who ignores the call of the leaders of this constitutional movement and goes after the castrated ‘all-India’ leaders;

– one who opposes this movement;

– those who do not let others join the movement and themselves do not participate in it;

– one who pleads for the cause of the foreigner;

– one who supports the wrong policies of the alien government;

– Those government employees-including policemen – who do not realise the significance of this movement and adopt a non-cooperative attitude;

– those acting at the behest of outside powers who try to create divisions among the primary organisations of the movement and thus aim at crushing it ultimately; and

– those non-Assamese residents of Assam who, while not participating in the movement, criticise it.

If you come under any of the above categories, and end your life! If you do not, then spread this message by getting copies of it made. Otherwise the tribe of the ‘bastards’ will multiply, and Golden Assam will come to nought. Long live Mother Assam!

This is the overt manner in which the Assamese people are made to toe the line. Being labelled a ‘bastard’ appears to be synonymous with being ostracised socially – a painful prospect for any local inhabitant.

The speed with which the agitation has gathered strength, and the seemingly insoluble problem the government in Delhi is confronted with, are alarming indicators of what lies ahead. Mrs Gandhi, it is reported, wants to withhold a stern clamp- down until after the Assembly elections. By then, if events in the North-east are an indication, it may be too late.