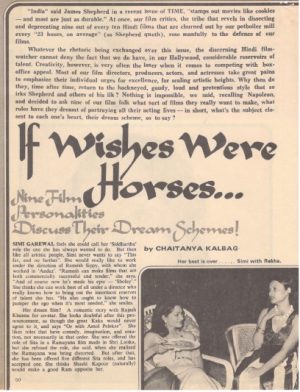

If Wishes Were Horses ..

Published date: 1976, Stardust

“India” said James Shepherd in a recent issue of TIME, “stamps out movies like cookies – and most are just as durable.” At once, our film critics, the tribe that revels in dissecting and deprecating nine out of every ten Hindi films that are churned out by our potboiler mill every “23 hours, on average” (as Shepherd quota), rose manfully to the defense of our films.

Whatever the rhetoric being exchanged over this issue, the discerning Hindi film-watcher cannot deny the fact that we do have, in our Hollywood, considerable reservoirs of talent. Creativity, however, is very often the loser when it comes to competing with box- office appeal. Most of our film directors, producers, actors, and actresses take great pains to emphasize their individual urges for excellence, for scaling artistic heights. Why then do they, time after time, return to the hackneyed, gaudy, loud and pretentious style that so irks Shepherd and others of his ilk? Nothing is impossible, we said, recalling Napoleon, and decided to ask nine of our film folks what sort of films they really want to make, what roles have they dreamt of portraying all their acting lives – in short, what is the subject closest to each one’s heart, their dream scheme, so to say?

If Wishes Were Horses …

Nine Film Personalities Discuss Their Dream Schemes!

SIMI GAREWAL feels she could call her ‘Siddhartha’ role the one she has always wanted to do. But then like all artistic people, Simi never wants to say, “This far, and no further”. She would really like to work under the direction of Ramesh Sippy, with whom she worked in ‘Andaz’. “Ramesh can make films that are both commercially successful and tender,” she says. “And of course now he’s made his epic – ‘Sholay’.” She thinks she can work best of all under a director who really knows how to bring out the innermost reserves of talent she has. “He also ought to know how to pamper the ego when it’s most needed,” she smiles.

Her dream film? A romantic story with Rajesh Khanna as a co-star. She looks doubtful after this pronouncement, as though the great Kaka would never agree to it and says, “Or with Amol Palekar”. She likes roles that have comedy, imagination, and emotion, not necessarily in that order. She was offered the role of Sita in a Ramayana film made in Shri Lanka, but she refused the role, she said, when she realized the Ramayana was being distorted. But after that, she has been offered five different Sita roles and has accepted one. She thinks Shashi Kapoor (naturally) would make a good Ram opposite her.

Simi’s real ambition, however, is to portray the role of Jennie Denton in ‘The Carpetbaggers’, that blockbuster book by Harold Robbins. She raves about Jennie’s characterization for five minutes: her being raped, her days as an exclusive call-girl, then as an actress, and finally as a nun in a convent. “What a rage,” Simi sighs. What a pity Salim-Javed had not thought of Jennie yet.

SUNIL DUTT, rugged he-man risen from the ashes of oblivion, says he does not have any dream scheme nothing he could describe as his most ambitious project anyhow. “I never want to believe that I’ve made the best film I ever could (as a producer) or that I’ve given my best performance ever (as an actor).” he explains. “Ambition is never-ending. The day my dreams come true; I will reach a dead end.” Sunil agrees most of his recent films have not exactly been dream films. But he had to move with the times, he defends. “I have to live,” he pronounces. “If I hadn’t made it, you wouldn’t be writing about me.” Point. Dutt Saab is none too happy about ‘Nehal Pe Dehal’, but he asks me to try and recall the truly artistic films he had acted in long ago: ‘Milan’, ‘Sadhana’, ‘Gumraah’, and ‘Ek Hi Rasta’, not forgetting ‘Mother India’. He played romantic roles then, he smiled. But if he did such ‘soft’ roles today, he tells me, his star image would evaporate. “Our films have been deteriorating thematically,” he agrees, “but this cycle would have ended soon. Aren’t more socially committed films being made today? We were making films that dealt with topics that do not exist here. Our creative urges were stifled.” But, given the choice, Sunil concludes, he – would like to make a film that “says something” the kind of film that William Wyler and David Lean made. “Wyler is closest to my heart,” Dutt Saab sighs. “Look at ‘Ben Hur’. Look at ‘Roman Holiday’.” Look at ‘Nehle Pe Dehla’.

SHABANA AZMI, poet’s daughter, has not really got an encore after ‘Ankur’. She has stopped counting the laurels she earned for her portrayal of Lakshmi in that. film. “Nishant’ was not similarly acclaimed, and a few other films that she has done since then were, to put it mildly, unimpressive.

Film people, therefore, concluded that Shabana ought to have remained in the off-beat film circuit. She would never be comfortable in a “commercial’ set-up. they figured. Shabana herself agrees that she has given her best performances to date under Shyam Benegal’s direction. But the battle (in her mind) on whether she should stick to Transitional Cinema or descend to potboilers had been fought long back, she insisted. Even now, she says, “I think my performances in “Fakira’ and ‘Karm’ are very good, Wait and see, and don’t forget that I’m still making off-beat films.” Shabana stars in two films directed by Basu Chatterji: ‘Swami’ and ‘Jeena Yahan’: the latter, she says, is the most exciting subject she has ever encountered. “I’m not very glamorous, or frivolous,” she says. “I have acting ability, and so I get a lot of films which are woman centered. I don’t think I am immersed enough in commercial films to have lost my sense of artistry.”

Shabana Azmi’s dream film, her most ardent acting wish, is to enact the role of Scarlett O’Hara in “Gone with The Wind’. “Nowhere else have I noticed a similar role,” she enthuses. “No other character has the opportunity to display such a wide gamut of emotions.” And Shekhar Kapoor nodded approval.

SHYAM BENEGAL, maker of the Hyderabadi classic ‘Ankur’, says he can never really make a film he thinks is the best. “No Indian filmmaker can afford to overreach the limits of marketability,” he says in his office at Jyoti Studio. “The only ideal situation exists only in Eastern Europe and the USSR, where the truly artistic director can afford to innovate and experiment without fear of commercial repercussions. State-sponsored cinema is the only environment in which truce cinematic genius can flower.” Here, he says, a director must be conscious all the time of monetary feasibility “I can easily sit down and think of a film which will be an artistic blockbuster and cost two or three crores of rupees. But will I ever get such financial freedom?”

Idealism has for long been infecting our film-makers, Benegal feels. “The fruit always looks sweeter in the other man’s orchard,” he recites. The creativity in an Indian film is determined by market conditions. says Shyam. These are features of any laissez faire economy. “I don’t think I can think of making a dream film now,” he ends. But his fourth film, which he has just started, appears to be based on a topic story very close to Shyam’s heart: the film is about the life and times of a film actress, and is based on Hansa Wacker’s life. Hansa, as we all know, was one of the Marathi screen’s most popular heroines. In fact, Benegal does seem to be making films close to his heart most of the time. But then he has not really had to compromise with commercialism, and in addition, his films have appear-ed at a time when Indian audiences are slowly beginning to understand and appreciate a better kind of cinema.

“If there is anything I have to hate,” NADIRA said, “it is being type-cast. After ‘Shree 420’ I was offered similar roles for a couple of years. They wanted me to play a madame. Being a screen mother does not suit an artiste of my zest. It contradicts my dedication to my work. It is very important for me to project something deeper than shallow maternal emotions,

“After Julie’s success, people now badger me with the same kind of roles. The Indian nary who is very phoner – the Anglo-Indian mama. It is not fair!” Nadira finished. “I’m very emotional, and my capabilities have never found free reign in those terrifying, petrifying mother roles. I can play emotional roles, bend my shoulders, look decrepit. But will anyone give me this kind of a chance? I know our films are hero-oriented, and male-character-actor oriented, but for Christ’s sake, why doesn’t someone come around to giving a female character actress a whopping good role? What can a daredevil, imposing, hero’s mother does except cry for him with larger tears?

“I would like very much to play the kind of roles Meena Kumari did towards the end. But all this talk is pointless. Will a film like “The Graduate’ ever be made here? Will ‘Whatever Happened to Baby Jane’ ever be made here?”

Nadira thinks she gave her greatest performance in “Insaaf Ka Mandir”, where she played a mother for the first time – and Sanjeev Kumar’s mother, at that. But most of her intense performances never make it to the screen, she scowls. “Sometimes I’ve given a beautiful scene, and for some reason (I won’t mention the obvious reasons) it lands on the floor of the editing room. That bugs me, I do not care for the length of the role. I care for its intensity. I have a feeling that after “Julie’ I’ll get a lot of good roles.”

Nadira described a scene she had done for ‘Aashiq Hoon Baharon Ka’. It was a beautiful scene, she said. and she was very happy with it. “The audience is getting cleverer and cleverer,” she said, “When ‘Bhanwar” was released after “Julie’, hundreds of my fans wrote in to reprimand me for having done that role. So, even if the offers flood me, I think I will do four good roles a year. and live well, and above all, keep my fans happy. And” she ended, puzzled, “most of them are men!”

So, Nadira, that terrific Maggie in ‘Julie’, wants to do “soft, soft, roles. More effective roles, Roles in which there are moments when the character feels it would be better to choke than bawl.”

Towards the end, Nadira slips into despondency again. “What’s the point of this talk?” she asks. “Will these films that I do so much want to do ever be made?”

I.S. JOHAR, joker in the film pack of cards, was not in a particularly humorous mood when I visited him – with a blanket drawn up to his chin, he told me he felt like “a stale joke”, “I’m totally different from what I’ve made myself out to be,” he intoned. “I have never essentially wanted to make comedies, but today Johar symbolizes the clown, the slapstick-maker. I never wanted to make a Hindi film, because the industry here is worthless at its best. Circumstances and lack of self-discipline made me saunter, as it were, into Hindi filmdom.” Why continue to hide his light under a bushel of inanities? “Films were the easiest method for making money.” Johar insisted. “Every- one is a third rater here, and I, being a little above being third-rate, made millions. I had a modicum of intellect.”

“My ambition has always been to make films which showed the ills of our society – the absurdities of Hindu orthodoxy, our backwardness, the stupid ideas we have harbored, like the theory of karma. And so, I made ‘Nashik’, You must realize that I am very patriotic, therefore anti-Indian. There is no contradiction in this. I wanted to de-educate my countrymen. and this was misunderstood. The Censors banned Nasik’.

“Everything in this country revolves around cults. I wanted to make films against the Rasputin’s of India. But I was a voice in the wilderness – even my most highly educated and intelligent confreres believed in these absurdities, totally.” And so, because “What I wanted to do was impossible, I decided to make money, and sing the glories of our idiosyncrasies, and of our Rasputin’s.”

Johar is certainly not modest about his caliber. “I firmly believe that there does not exist a single director in the Indian film industry who can come up to my caliber,” he says. “But I exclude Satyajit Ray, For various reasons.” “I’m not satisfied with catering to the tastes of a small crowd,” he goes on. “It’s very easy for me to make films like Benegal, Hrishikesh. But these films are seen by a minority. Those Transitional Directors are all dishonest. They too want to make money. I admit that that is my aim. They don’t.”

Why not try and break out of this impasse? “Look, I’m graded here as a C-class actor. But I acted in ‘Harry Black and The Tiger’, and believe me, I put in my best work there. I was nominated as the best actor in England by their Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences – the British Oscar. Let me tell you. I care two hoots about Indian awards.”

And so, like Picasso, Johar says, he takes “sadistic pleasure in fooling his countrymen now, cashing in on their stupidity.” Which is why he makes stupid, insane, slapstick films. But even that could be frustrating. for people fail to notice his sadism. So today. Johar has turned to the production of television films, because “I have no commitments to the box-office, I am totally in charge, and I have no finance to worry about.” A sad transition, from Harry Black to the idiot box.

N. SIPPY, the film producer, leans back in his executive chair and tells me he has always made films he has really wanted to make. “All of them have emotional themes,” he says, “The Indian audience likes emotional topics. My films have been basically good – they do not belong to any school or formula. I provided suspense in ‘Woh Kaun The’ and ‘Gunnam’, box-office ingredients in “Shatranj’, emotional appeal in ‘Haar Jeet’,”

But is the public ready to accept good cinema, asks Sippy. Would they agree to the hero or the heroine dying at the end of the film? He says his aim is to make films with themes that the public understands – he wants to speak their language. All idealistic films, he says, reverting to my original question, have gone over the public’s heads. The people want escapism, entertainment, at the lowest cost. Art is beyond the successful filmmaker’s abilities.

N.N. Sippy’s ambition is to make a “tragic love story” – the kind that has both the lovers dying in each other’s arms at the end. “A true love story always ends in heartbreak.” Sippy defines and goes on to list the films that have influenced his thinking in this regard the most: ‘Love Story’ and ‘Brief Season’, “I have dreams,’ Sippy ends. “But no story. I have been searching for a truly sad love story, and it has been a fruitless search.”

When I leave him, Sippy is trying to untangle one more mix-up over the release of his latest film “Fakira”. It is sad “Fakira’ is not a ‘Love Story”.

SHAMMI KAPOOR was wrapped in a recording session when I met him. He was watching R. D. Burman watch the orchestra belt out the title music for the latest film he has made. The take was okay, and then Shammai and Pancham sat down to play two long games of chess. His ego buttressed by two spectacular wins against Pancham, Shammi told me he was ready for the Inquisition. The Inquisition, however, was a five-minute affair. Shammi Kapoor had no dream scheme, no story he always wanted to film, no artistic aspirations as of now. “I know the environment I’m in,” he said. “And I want to make ordinary, nonsense films for some more time. This is my third nonsense film. Only when I am financially ‘up there’, then perhaps I might someday try out those aspirations I harbor within me to be like DeSica or Kurosawa. Right now, I do not think I can even make ‘Sholay’. I am not yet there, on the graph. I am not yet there where it counts, and even if I wanted to be another Raj Kapoor overnight, well, you know that proverb about wishes being horses ……

“Shammi thinks the best films he has acted in are “Professor’, ‘Brahmacharini’ and ‘Pagle Kahin Ka’. But in his filmmaking future, he does not foresee sudden brilliance. “I want to take it slowly, steadily. There is a lot of time. A lot of hope ……

Last of all (and not least of all, as the posters would say), HRISHIKESH MUKHERJEE, revered film director, maker of ‘Anand’ and ‘Guddi’, tells me he would like to make films that are different from the run of the mill. But, he says, echoing Sippy, he must restrict himself to a language that is understood by the masses. “Like Enid Blyton”, he says, “who used a maximum of one hundred common words in all her books.” But he cannot really do a daring film, he says, for reasons obvious, “Even if I had the wife getting attracted to the other man,” Hrishi-da says, “the audience wouldn’t accept it.”

Assuming he were given a free hand, Hrishi says, he still would not be able to make a film like Satyajit Ray. But he has dreamt for a long time of making a film that would trace the rise of a common man – for instance, a biographical film that would show how every ordinary people can and have climbed the ladder to the dizzying heights of success. He wanted to make films about people “like you and me” like Nadia Comaneci, he says, which means he has been watching that 14-year-old Romanian whiz-kid at Montreal on his TV set.

Hrishi-da says he also wants to make films about topics like the clash between scientists and the bureaucracy, for example. But “I don’t want to make a New Wave film,” he ends. “The New Wave” films have been mostly mediocre. Essentially if I made a very good film, I would try to retore the credibility of the film medium,”

What do the replies of these nine people reflect? Essentially, that they are all sad about their professions. Not because they are being given a rotten deal, but because they have, each of them, dreams that do not seem capable of being fulfilled, Which leads one to conclude that, even assuming that the right people combine to try and make the really ideal film, there would still be the hurdle of the audience to cross, Not until our audiences begin to develop the sensitivity needed to ingest better cinema can our truly talented film-people give off their best. Masterpieces are rare, but then, there’s always room at the top. Cinematically, all our directors and artistes and producers wallow in a morass of contradictions, of apparent brilliance versus evident insipidity. And one begins to wonder whether Napoleon was not really wrong.